On August 10th, 2010, the Salt Lake City Council voted to adopt the North Temple Boulevard Master Plan. A decade later, that plan would be used to displace at least three families from their homes. In 2019 the Kozo displaced two families, three years later the Chicago Street Townhomes displaced another. All three families were renters and long-time residents of the neighborhood, and none had any choice in the matter.

The connection between master plans and their consequences is often difficult to trace, and it is not surprising that here a decade stood between the two. When planners “plan” they do so in anticipation for future, almost always private, development. This is reflected in the plans themselves, the North Temple Master Plan, for instance, is meant to provide “a framework for land use and urban design decisions” which can “provide direction to decision makers, property owners, business owners, designers and developers regarding,” what the planners call “the community’s vision for North Temple Boulevard.” These quotes capture the basic functions of planning; planners construct a vision for a given space, which they then translate into zoning and design constraints which landowners must then abide by when developing their properties. Put more succinctly; planning regulates private development.

While this remains the core truth of land-use planning, a truth it readily admits, it also lays claim to being representative of a “community,” with the North Temple Plan, for example, claiming to represent “the community’s vision for North Temple Boulevard.” The “community” in question here are whatever individuals could make it to one of the city’s 4 public workshops and whatever “property owners and key stakeholders” the city decided to meet with. In the plan itself, the three groups that make up this supposed “community” are “residents,” “property owners,” and “stakeholders.” Stakeholders is a purposefully vague term but often captures nonprofits, business associations, government officials, and the like. While this is not a holistic critique of plannings claims to represent some semblance of “community,” the term community is used as a stand in for neighborhood. Here, community implies the existence of enough social connections within a neighborhood to constitute a “community” which could then have a vision for what they want their neighborhood to be, while this might today exist between some neighbors, it is certainly not at the scale necessary to make the sorts of claims made in this plan; furthermore the vision the planners construct is static, being made once and then held immovable for decades to come, a clear reduction of what should be dynamic and ongoing process. These leaps in logic are important for planning because they give its practice a veneer of legitimacy, if they’re simply representing the vision of the community then how could they be wrong? This veneer is also important for property owners, who are then able to use this supposed “community vision” as justification for their development efforts, hiding their real, private, reasons behind their actions.

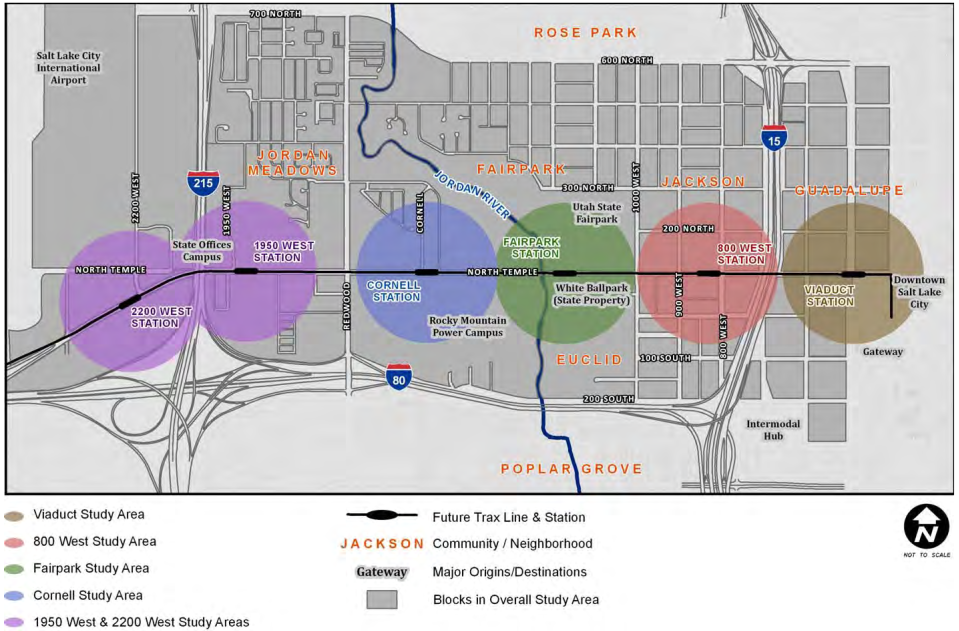

So what did the planners claim the community’s vision was? Transit-Oriented Development (TOD). While the plan was being developed, the Utah Transit Authority (UTA) was connecting their TRAX Light Rail network to the Salt Lake City International Airport, creating 6 new stations along North Temple Boulevard. These stations became the focus of the new North Temple Master Plan, which established 5 Station Areas, each covering a half mile-radius around the TRAX Stations. Within these station areas, the plan laid out zoning changes (zoning is the tool planners use to regulate land-use), creating new regulations to “promote a diverse mix of uses,” the golden standard of which seems to be putting shops on the first floor of apartment buildings (thereby mixing residential and commercial uses). The plan resulted in the currently existing Transit Station Area (TSA) zoning districts, which range from TSA-UN-Core (UN stands for Urban Neighborhood) for parcels closer to the stations, to TSA-UN-Transitional for parcels which are further from the stations. Both of the gentrifying redevelopment projects, the Kozo and the Chicago St. Townhomes, are located in TSA-UN-T zoned areas.

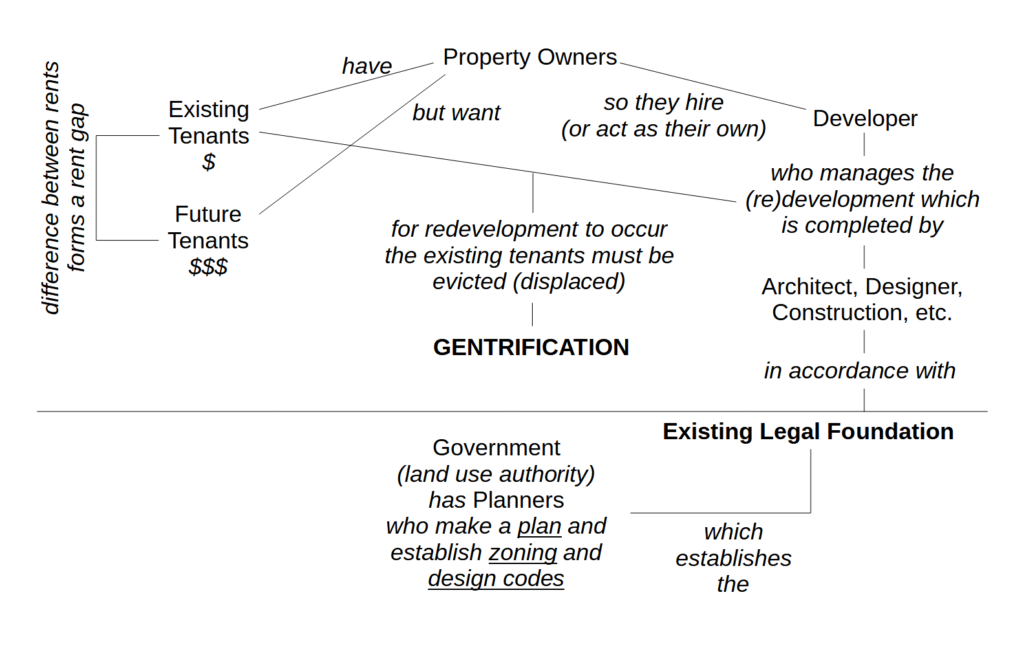

Zoning is a dry subject, but if it wasn’t for this rezoning (changing the zoning), these instances of displacement couldn’t have occurred as they did. Before we tie planning and rezoning to gentrification, however, we need to explore one last factor. All three of the families that were displaced because of this plan were renters. Utah has notoriously few protections for renters, but even if this wasn’t the case, the law has a built-in bias against them. Renters don’t own property the properties they live on, and when push comes to shove, whomever owns the property always wins. Our society is governed by capitalist social relations, in which control of production (including the production of space) is in the hands of property owners. This can be seen very clearly in space; whoever owns a parcel of land controls what happens on it. That being said, there are two important caveats to this, although neither undermines its ultimate truth; first, as previously discussed, land-use planning limits the potential uses of a space and sometimes defines broad design requirements, and second, property owners, like us all, are beholden to the laws of value. While value, and its most common form in contemporary capitalist society, money, is highly complex, when it comes to spatial development, the basic logic is that if a development project doesn’t promise to produce more value than it took to construct than it doesn’t happen, basically there needs to be some promise of a return on investment.

Both caveats are important to the North Temple situation because the North Temple Master Plan addressed both. The Master Plan’s rezoning upzoned the parcels it affected, meaning it allowed denser and more varied construction than what was allowed under the previous zoning code. While far from completely deregulating development, upzoning often allows far more freedom for landowners looking to redevelop their properties. With the parcels that the Kozo and Chicago St. Townhomes redevelopments are located on being upzoned to allow for TOD, the previous limits on rent accumulation were lifted, and the difference between the amount of rent that the landowners were currently collecting became a fraction of the new potential rent they could collect if they redeveloped their properties to fit the new, denser, zoning codes. This difference between existing-rent-accumulation and potential-rent-accumulation, is called a rent-gap. Where previously, the zoning limited the amount of rentable housing units a property owner could build to one or two units per parcel, upzoning increased that limit 10x. The Kozo at one point planned to build over 300 units on the same amount of land that once housed a dozen homes. The difference in rent-accumulation between potentially renting 300 units and currently renting 12 created a rent gap that could only be closed through eviction, displacement, and redevelopment.1

In the cases of the Kozo and Chicago St. Townhomes, this gap was further increased by the relatively affordable rents the displaced families were paying. Caught between the promise of more units renting at ever-increasing prices and property owners whose first and primary interest in owning property is in using it to accumulate value through rent, three families were displaced, victims of property-owners looking to close the rent-gap, caused by upzoning, by redeveloping their properties. The North Temple Master Plans rezoning of Rose Park/Popular Grove laid the legal foundation for the neighborhood to be gentrified by property owners and developers.

On North Temple this process is glaring clear to see, but its conclusions ring true broadly, government is more a friend of property than its adversary. But we can perhaps see the outlines of whom some of the different actors are in gentrification:

1A quick note on density, the problem with this plan and the development projects mentioned here are not their density, but that they displaced people. The buildings might be ugly and often times inhuman, sure, and that is a critique in-and-of-itself, but it is a subordinate critique to the negative effects these projects have had on peoples lives.