Utah has enjoyed relative prosperity and economic stability despite continued capitalist economic crisis. While the working class still bears the brunt of any such crisis, the state economy, as much as one can be defined against the national and international capitalist economies, has remained strong. This strength can be ascribed to staunchly pro-business politics (which range from lax regulations to massive government subsidies for business), large regional institutions with incredible wealth,1 and a diverse economy boasting extractive, service, logistical, tourist, agricultural, and financial appendages. Even in a world economy that is ever more closely knit, and in which economic crisis is ever more widely felt, the capitalist class in Utah has flourished and the state economy has continued to grow. But as the frequency and severity of capitalist crisis increases, this prosperity has come under threat. Within the very process of capital accumulation, that all powerful “profit” from which all capitalist logic is derived, there lies a tendency to economic crisis. While far more can, and should be said on it, the long and short context of this article is that the rate of profit of capitalist enterprises is, and has for many years been, in decline. This tendency of capital has been known for a century now2 and continues to be true.3 For this article, however, the most important take away from this theory of capitalist crisis, is that it accounts for the state’s growing interventions in the otherwise “free-market” economy. These interventions have created a state of affairs where those advocating for truly “free” markets have been pushed to the political and economic fringe, constituting a laughingstock for liberals and leftists alike. The regularity of state intervention has resulted in the creation of what many refer to as a “mixed-economy,” sometimes recognized further as Keynesian economic policy. These policies, which range from inflation to deficit financing to public works, allow states to intervene in the private economy on behalf of the private economy.

But this article is not meant to capture the totality of state intervention in the Utah economy, rather its focus is on the state’s economic interventions in space. All industries, in fact all of society, necessarily exist in space. Whether that space is a factory, mine, office, mountain, road, or store, in order to exist, they must occupy space in some capacity. It is here where the ruling class, both those formed into private enterprises and those in public ones, have, through the course of the past century, come to realize the importance of urban planning. Urban planning, which in the planning practice of today can be broken into two disciplines, transportation planning and land-use planning, has become the state practice of ordering the spatial dimension of capitalist growth, attempting to connect and delineate, in general terms, the particular uses of particular spaces (think zoning and its demarcation of residential, commercial, industrial, etc. zones). Urban planning in the contemporary capitalist metropolis has proliferated in the past century at the same time that rolling economic crises have demanded state interventions in the “free-market” capitalist economy. At the same time, however, “the capitalist state is not to compete in the market with the private capitalists it serves, its contribution… must take the form of public spending which is useful to capital.”4 It is, then, in this tendency of the capitalist state to intervene in the economy, but not in competition with private capital, that the actions explored here, taken by the Utah State, must be seen.5

In 2018 the Utah State Legislature created the Point of the Mountain State Land Authority6 and the Utah Inland Port Authority.7 These Authorities hold similar powers over land use as city planning departments, and were given the explicit mandate from the legislature to “plan” the development of their respective sites. In these two efforts, urban planning as state intervention reveals itself clearly, all while the developments show themselves to be simultaneously rooted in the larger capitalist mode of production, while being intimately tied with one another.

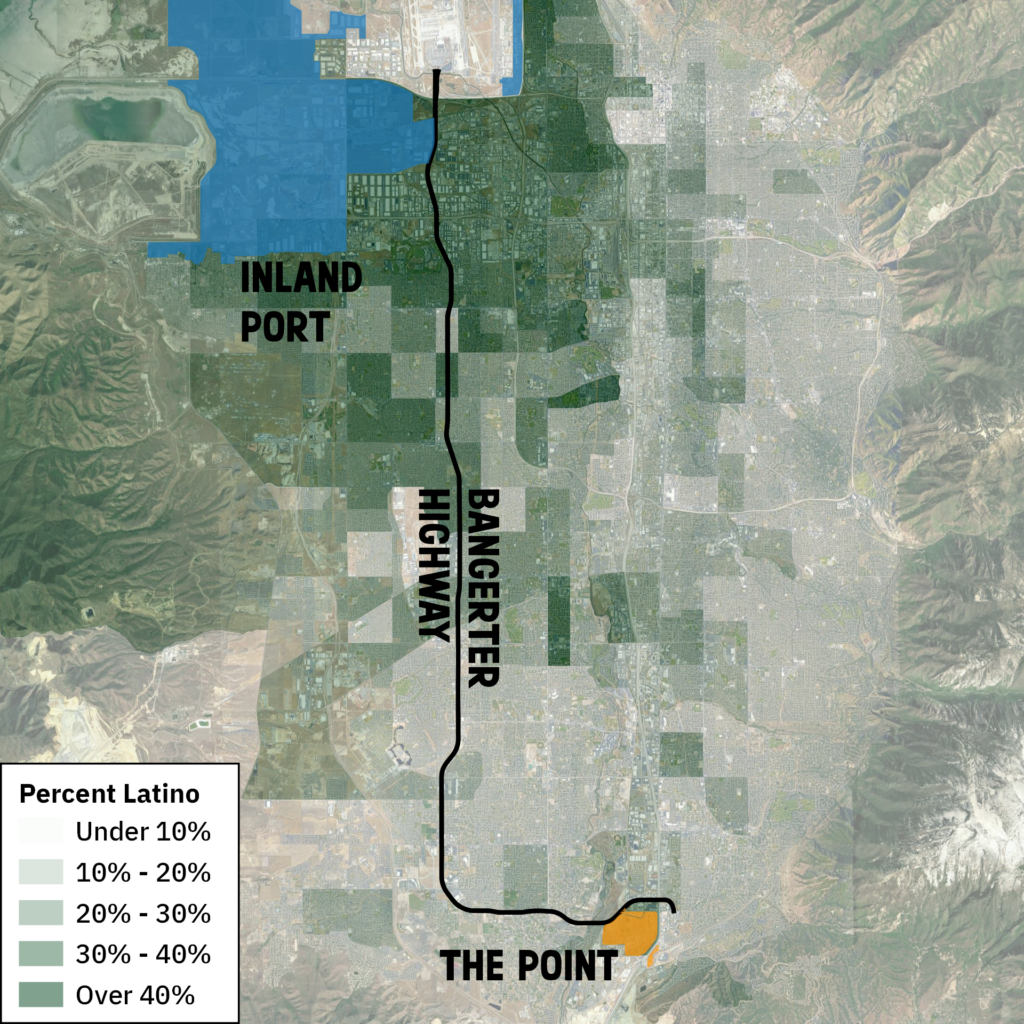

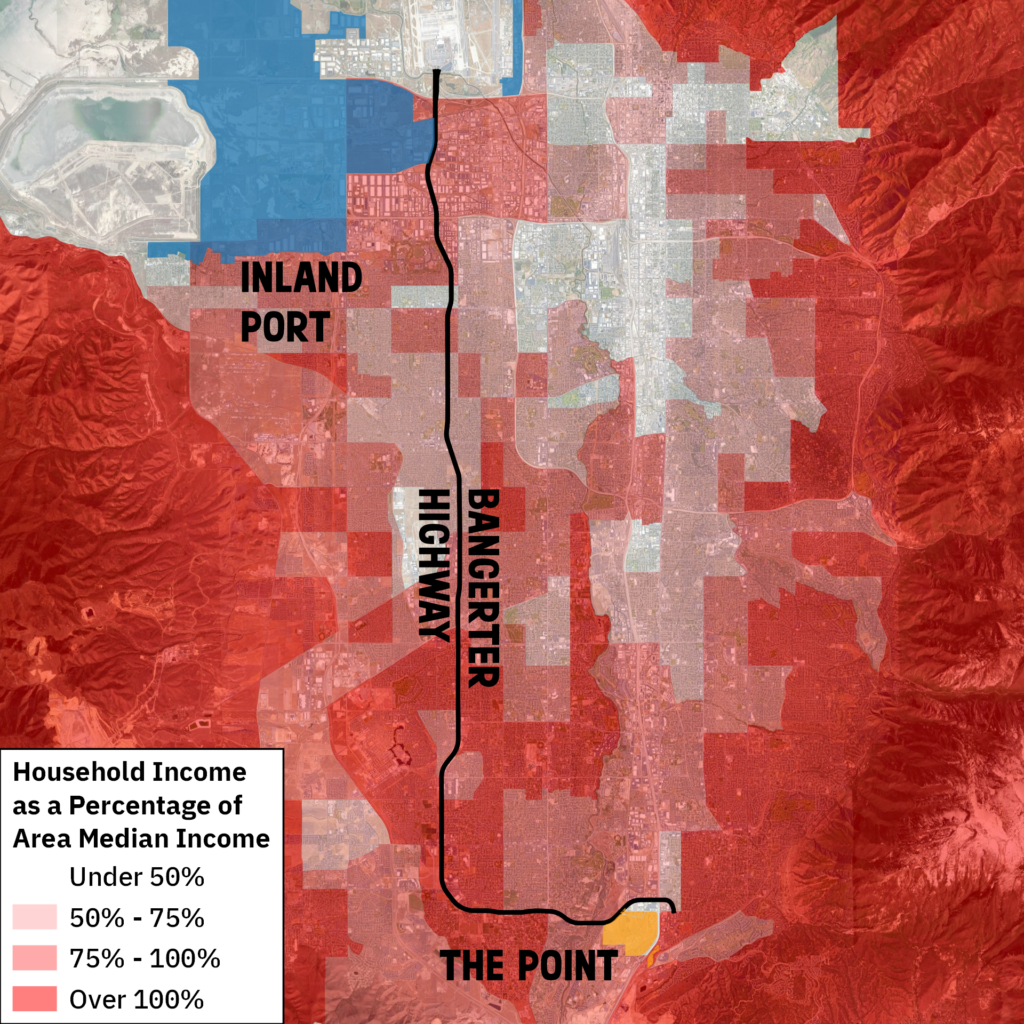

When the Utah State moved the state prison from the Point of the Mountain to a site which sits within the Inland Port boundaries, it freed up 700 acres of newly developable land in a highly valuable part of the valley. In order to fund the expensive relocation of the prison, however, the state leveraged the assumed, future taxable economic activity on the Point of the Mountain site, debt financing the prison move and tying its financial success to the successful development of the Point of the Mountain property. In turn, the prison, itself a source of value production8 and labor, sits as a major public capital investment in the burgeoning Inland Port. The larger context of these state-backed efforts is hard to overemphasize, as both serve fundamental purposes in capitalist society. Prisons warehouse reserve labor and populations considered to be surplus, and reflect the racialized working class, with Latino, Black, and Indigenous prisoners being overrepresented in Utah’s prison population.9 Alongside this, the transportation, warehousing, and logistics efforts of the future Inland Port, will play a key role in local, regional, national, and international commodity and capital flows. The Utah legislature, correctly identifying these essential aspects of capitalist society, has heavily invested in them, seeking to concentrate and fix the flow of capital through Utah, specifically along the Wasatch Front. The Point of the Mountain development, on the other hand, is meant to cater to more “forward-thinking” capital; high-tech, urban, and educated. The Point (as those involved refer to it as) seeks to orient itself towards what it calls the “21st Century innovation economy”10 complete with a highly-paid, highly-trained, and highly-educated workforce. While the hinterlands receive an ever deeper entrenched industrial and logistics industry, the white, upper-class suburbs receive a “vibrant urban center” for “housing, jobs, shopping, amenities, and open space.” Where the hinterlands will be further polluted by commodities moving through the manufacturing, warehousing, and freight infrastructure fixed therein, the Point stands as an unharmed recipient of this expanded infrastructure for commodity circulation; where the working-class suffers, the upper-class gains. This duality reflects the necessary class division of capitalist society, here reflected in both space and its planning. The Inland Port and the Point sit at opposite corners of the Salt Lake valley, nestled in core working class and upper class neighborhoods respectively, and they hold nearly opposite land uses. And yet, both are consciously made and spatially planned economic interventions taken by the Utah State. Where The Point seeks to attract real estate, financial, and commercial capital, the Inland Port seeks industrial and transportation capital.11 For the white upper class neighborhoods in south-east Salt Lake, the state is backing a project meant to “encourage sustainable growth, reduce driving, and improve air quality,”12 while for the diverse working class neighborhoods in the north-west hinterlands, they see space for “developing and optimizing economic project areas and logistics-based infrastructure.”13

But the Utah State has not only become more involved in matters of land-use planning, it also acts through the Utah Department of Transportation (an agency which is completely at the command of the Utah State). As part of the state’s support for these land-use projects, the Utah State has invested billions in transportation infrastructure as well. For the Inland Port, two nearby highways are currently in the process of expansion; the I-15 and Bangerter. The I-15, an interstate highway which stretches across and beyond the state, is already set to connect the main Inland Port site in Salt Lake with a developing satellite port in Spanish Fork (one of several planned).14 The Bangerter Highway, currently under construction to remove the stop lights at intersections that proved so dangerous that an intersecting road had to be closed down in 2021 after almost daily crashes for a month,15 is placed with the Inland Port at its northern end and the Point at its southern, as though it were made precisely to connect these two development projects. Bangerter’s expansion, which explicitly refers to the Inland Port in its justification, is planned to displace approximately 281 families across the entire valley, with the vast majority of those, 241, to take place in West Valley City,16 in the working class hinterlands of Salt Lake. At the Point redevelopment site, the state tasked the Utah Transit Authority (UTA) with developing a transit component to compliment the redevelopment, but after UTA chose bus rapid transit (BRT) the state stepped in once more. In 2022 the Utah legislature passed a bill giving the Utah Department Of Transportation (UDOT) control over all “fixed guideway capital development projects that include state funding” (fixed guideway more or less means any project that has a large infrastructure component),17 going so far as to even call out in the bill the development of transit at the Point of the Mountain as something UDOT now has control over, putting an additional $2 million towards the transit study as well. With this bill, UDOT, under the direction of the state, scrapped UTA’s finding for BRT at the site and even forced consideration of the technology used by the politically connected Stadler Rail, which has already received potentially over $10 million in incentives from the Governor’s Office of Economic Opportunity.18 While the outcome of the study19 is still yet to be determined, the desire of the state is clear, likely inspired by the private capital investment spurred on by the S-Line20 and other light rail projects in Utah and across the nation, they want rail at the Point, and they won’t stop till they get it. For what it’s worth their logic on the matter is sound, rail will certainly attract far more private capital than any bus could, something both the S-Line and the Green Line TRAX along North Temple in Salt Lake City have proven.21 The Utah legislature took a risk debt financing the prison move on the hope that The Point’s redevelopment would pay it back in time, and they’re willing to throw millions more towards public infrastructure and private incentives to court the capitalists who could make it happen.

In these state-backed projects, the role of the state as the defender and guarantor of capital becomes clear. By establishing large-scale state-backed development projects, tied together by massive investments in transportation infrastructure oriented towards capitalist industry, the Utah State has used urban planning to intervene in the regional economy. Far from letting the market decide, the state has realized, as many others have previously, that capitalism is not a self-sustaining mode of production, and that if left to its own internal logic, it will march straight into crisis. In a bid to avoid the worst of that tendency for local capitalists, the Utah State, itself largely made up of capitalists, has set out to utilize urban planning towards these class ends. The resulting planning practice can therefore only be seen as capitalist urban planning, that is, as an urban planning practice that orients its work towards the continued dominance of the capitalist class and the continuation of the capitalist mode of production. While one could long have said this about urban planning in general, the specific role that urban planning takes here in the capitalist economy demands this conclusion to be drawn out anew, for it suggests that capitalism, too, demands some degree of planning. While urban planning is distinct from economic planning, insofar as the economy exists in space, urban planning does affect many aspects of economic activity; where it is situated, what transportation infrastructure can be utilized, what other industries are sited nearby, etc. The novelty of these recent interventions by the Utah State lie in its specificity, its ability to utilize urban planning not as a vague delineator of generalized land-uses, but as a specific actor, consciously choosing what industries, and what class, an area of land is developed for. The role taken by the Utah State in the Inland Port and The Point redevelopments is key to understanding its interventions. The Utah State, here, is not competing with private capital, but rather, through urban planning, the State is setting the stage for private capital’s success, modifying the conditions of space to better facilitate continued capitalist accumulation.

The utilization of urban planning in this way, however, begs the questions; can urban plannings interventions in the capitalist economy be seen as an act of economic planning? Key to this exploration is identifying when intervention, the sort which capitalist states have long been involved in, becomes planning. We can, without a doubt, assert that these recent urban planning efforts by the Utah State constitute interventions in the economy, establishing a new port for commodity circulation, expanding transportation infrastructure, facilitating private redevelopment of land, etc., but does this constitute an effort to plan economic activity? In a specifically spatial way this would appear to be the case; since the advent of land-use planning, capital has not been free to site itself wherever it desires, but this has often been to its advantage. Relinquishing authority over land-use to government bodies has freed private capitalists of the tricky work of mediating between the activities of different capitalists and their land-uses. Likewise, capitalists can largely wash their hands of any responsibility regarding the external effects of their activities (pollution, noise, etc.), for land-use planning creates for capitalist industry legal standards, which, if met, can be used to defend their actions on the grounds of legality (a similar relationship can be seen in regard to labor conditions and urban development in general). In this way, land-use planning as it is currently practiced regulates capitalist activity, but in a way that is both favorable to it and entirely in accordance to its forms and relations. Capitalist urban planning respects and validates private land ownership and regulates in a useful way the spatial development of capital. In respecting capitalist forms and relations, urban planning necessarily hinders its ability to sufficiently plan the activities which take place in the spaces being planned. True to this fact, the warehouses of the Inland Port and mixed-use redevelopments of the Point alike, will ultimately be in the hands of private capitalists acting on no-one’s orders but those of their own private desires and the compulsions of the market and the value-form.

So what does this all mean for the question of capitalist economic planning? Capitalism as a mode of production relies on certain economic forms and social relations; wage labor, the commodity-form, private ownership of the means of production, etc., and these are all things that capitalist urban planning does not address. However, any given capitalist industry is reliant on there being nearby sources of labor (residential zones), infrastructure to move commodities around (roads and rails), and a system of private land ownership (land-use law), and these are all things that capitalist urban planning addresses directly. The question, then, appears to be one of the State balancing a desire to consciously plan certain elements of the capitalist economy, while holding fast to the essential attributes of the capitalist economy which are antithetical to planning (value flows, labor force movements, land values, etc.). In this way a sort of economic planning does appear to occur, but at too high a level to really constitute a planned mode of production. Instead, the state is using urban planning to intervene and shape the spatial context within which capitalist processes take place. The significance of this for the specific examples explored in this article, lies not in the fact that the state itself is not running the warehouses at the Port, the trucks moving through it, or the housing, office, and commercial space at the Point as a sort of nationalized industry, but that the state is consciously creating, as much as it can within the bounds of the capitalist economy, a favorable context for specific capitalist industries in the lands under its authority, land which it consciously plans relative to the already existing distributions of race, class, land-values, and industry. Such a favorable situation must be consciously created by the state at this time, for through the course of capitalism’s functioning it threatens the very basis for its continued accumulation of capital. To return once more to the question of crisis, we find therein the rationale for these interventions as a counter-tendency of the state to the crisis tendency of capital. In the previous century, a more profitable capitalism could pretend that it could solve all its problems through its own internal processes, but as crisis after crisis hit, this notion showed itself to be false. What is now occurring in Utah, with the help of an urban planning practice seized upon by the Utah State, is nothing but this history of capitalist crisis catching up with Utah. Seen in this way, the Utah State’s use of capitalist planning (this partial economic planning achieved through urban planning) stands as a counter-tendency to crisis, a tool wielded over a certain part of the economy to consciously attempt to create the conditions for a more stable and profitable capitalism in Utah.

The implications of this analysis will not be sufficiently drawn out here, for it will take real opposition to these capitalist urban planning efforts to bring to light their implications for the class struggle in Salt Lake. What is clear, however, is the growing importance of workers in the logistics industry in the valley, which promises to only increase in size and influence. In light of this, the recent militancy of the rank-and-file UPS Teamsters, shows the capabilities of an organized working class, located strategically at key points in the circuits of value, to bring the capitalist economy to its knees.22 Furthermore, such an understanding of the state’s connection to private capital will prove necessary to adequately understand, and thus adequately confront, the Inland Port and highway expansion projects which threaten displacement, pollution, and harm to working class neighborhoods in the hinterlands. Finally, in better understanding the contemporary capitalist economy, revolutionaries can better understand the social relations and attributes which must necessarily be abolished in order to bring an end to the capitalist mode of production and establish a new, planned, mode of production. This analysis is also necessarily partial, but hopefully points to deeper truths in the political economy of society today. Capitalist crisis continues to persist and continues to provide opportunities for revolutionary action, should the working class find within itself the capacity to act. The interventions by capital and the state have shown themselves to be nothing more than the defense and entrenchment of the capitalist order of things, only the working class can ultimately overcome capitalist crisis and bring about a new mode of production.

1https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2023/07/16/lds-church-its-way-becoming/

2https://www.marxists.org/subject/left-wing/icc/1935/05/marxism.htm

3https://brooklynrail.org/2022/10/field-notes/The-Knife-At-Your-Throat

4https://www.marxists.org/archive/mattick-paul/1971/american-economy.htm

5A point of clarification; Utah State, here, refers to both the state in the sense of a political institution backed by violent force and a level in the US Federal Government structure

6https://le.utah.gov/~2018/bills/static/HB0372.html

7https://le.utah.gov/~2018/bills/static/SB0234.html

8https://salt801.com/articles/theory-and-practice/slcs-other-side-village-and-the-industrialization-of-homelessness/

9https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-utah.pdf

10https://static1.squarespace.com/static/583320c02e69cf0414285109/t/5a66412b419202b35beec2eb/1516650802694/Phase+2+Vision+Overview+for+web.pdf

11As an aside, but also further highlighting the increasing role of the state in matters of economy, the local partners of the lead developer of the Point of the Mountain redevelopment are also a major force behind the SLC Global Logistics Center which is developing acres of warehousing space at the Inland Port. Backed by the Utah state, these capitalist developer and real estate firms will profit massively from these two state-backed development projects.

12https://pointofthemountainfuture.org/

13https://inlandportauthority.utah.gov/about-the-utah-inland-port-authority/

14https://www.kuer.org/business-economy/2023-07-18/utah-inland-port-authority-approves-the-spanish-fork-port-project

15https://www.ksl.com/article/50226617/udot-closing-6200-south-at-bangerter-highway-after-jump-in-crashes

16https://www.bangerter3500to201.com/_files/ugd/2eab42_811e0a1c1cea433686657b3982a4c6d4.pdf

17https://le.utah.gov/~2022/bills/hbillint/HB0322.pdf

18https://business.utah.gov/incented-companies/

19https://udotinput.utah.gov/pointtransit

20https://deconstructsaltlake.noblogs.org/post/2023/03/03/vacant-luxury/

21https://deconstructsaltlake.noblogs.org/post/2022/12/13/planning-for-displacement/

22https://salt801.com/articles/news-and-events-analysis/report-back-strike-preparation-underway-at-slc-ups-hub/