Detroit: I Do Mind Dying presents itself as a Study in Urban Revolution. Throughout the book, authors Dan Georgakas and Maravin Surkin present the actions of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the subject of the book, in contrast to the emerging vision of New Detroit. Backed by the major capitalist firms and political interests in the city, the plans for a New Detroit as presented in the 1960s and 70s looks a lot like the urban visions of today, focusing on new buildings and amenities for the professional classes (yuppies):

The heart of the new program was a $350 million Renaissance Center with hotels, luxury apartments, office buildings, and quality entertainment facilities to be built on the riverfront, directly to the east of Woodward Avenue. The showpiece of the center was to be a 70-story glass-encased hotel with 1,500 rooms. Four 30-story office towers with banks as major ground-floor tenants would share the complex with the hotel. Contributions for the center included $6 million from Ford, $6 million from GM, $1.5 million from Chrysler, $500,000 from American Motors, and smaller contributions from more than 30 Detroit firms. The hotel, offices, and projected apartment dwellings were to be serviced by a variety of shops, restaurants, and retail stores.

This vision emerged in the 70s, when Detroit was in the throes of de-industrialization. Faced with runaway factories, where capitalist firms preferred to move their manufacturing facilities out of union stronghold cities, like Detroit, the city’s ruling class knew it had to envision a new city. While the particular vision of New Detroit they initially sought never quite materialized (the Renaissance Center and surrounding developments failed to attract additional capital investments, failing to “revitalize” the city), for a time a radical alternative was being constructed.

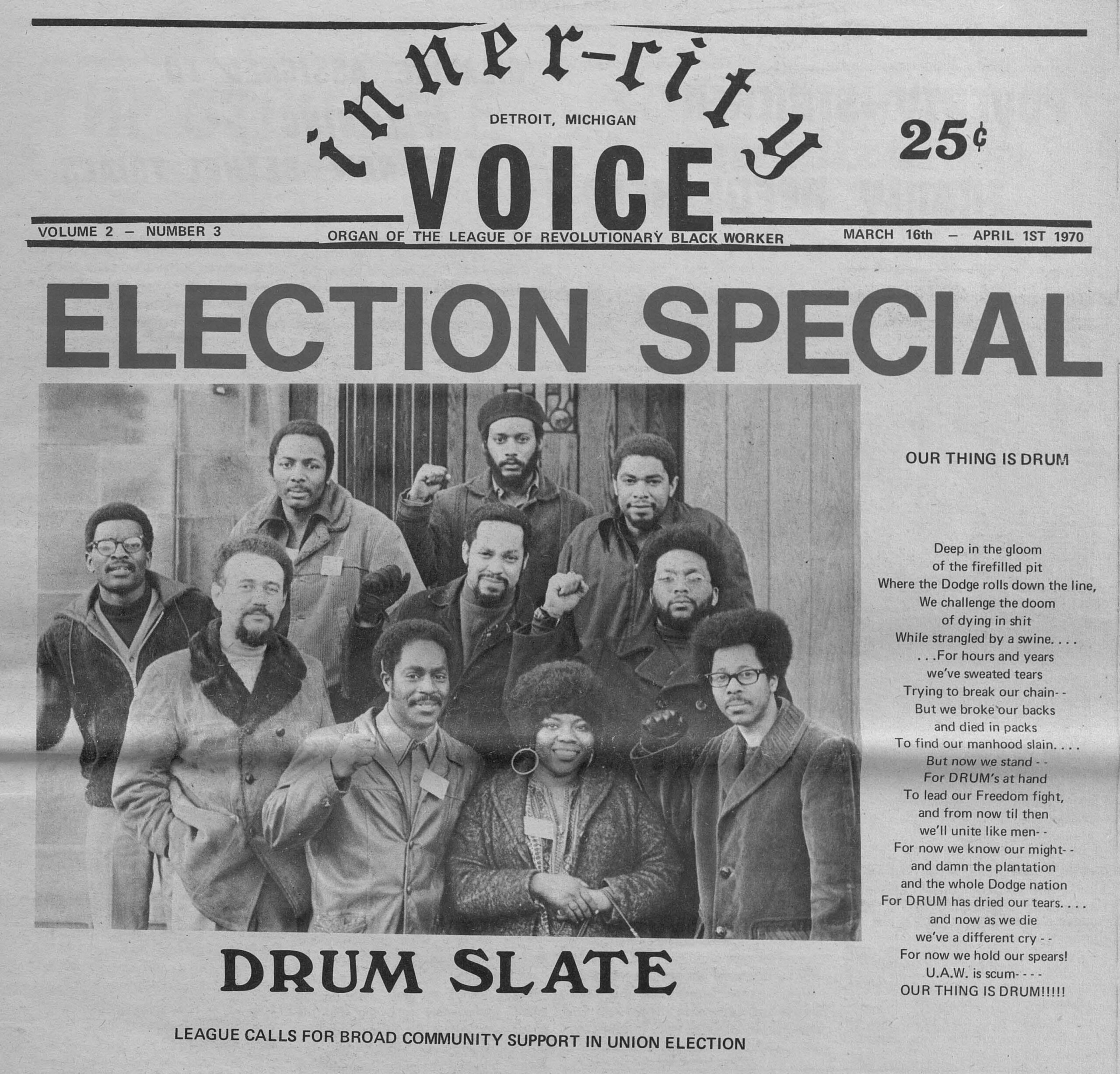

Rooted in the very auto manufacturing facilities soon to be shipped off, the Revolutionary Union Movement (RUM) grew out of the experiences of black workers in the unionized factories. Facing an increasingly reactionary United Auto Workers (UAW), the RUM’s sought to form militant cadres of workers to engage in direct action and class struggle on the shop floor. For a time they succeeded, building up and out, eventually creating the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. One of the League’s first successful efforts was gaining control of the Wayne State University paper, the South End. Reorienting the paper towards issues likely to be felt by Wayne’s predominantly working class student body, the League leveraged the South End to highlight both the racial and class-based struggles of Detroiters, including the organizing work of the RUM’s, and build international ties, placing local struggles in the context of international events like the ongoing war in Vietnam and the struggle of the Palestinians. Another branch of the League’s non-workplace organizing work included the Black Economic Development Conference (BEDC), which, unlike seemingly all contemporary economic development efforts, developed into “a call for black socialism.” Like many of the other formations in this history, BEDC was not long-lasting, but it did produce a publishing house and began to develop a vision of a different, anti-capitalist, form of economic development with local roots but a national reach.

A slightly different approach was taken by Judge George Crockett and attorney’s Kenneth Cockrel and Justin Ravitz. Each of these figures sat at the curious crossroads of legal practice and racial and class-struggle. Crockett has been a defense attorney for the Communist Party and been involved in numerous social movements. Cockrel also sought to use the courtroom to put racial and class oppression on trail, enlarging “the scope of the cases to involve the interests of a whole community or class.” Ravitz, too, became an elected judge; his “understood that we can neither litigate nor elect our way to liberation, but selective and serious entries into each arena can advance the building of a socialist society.” Serious and real victories were gained by the practice of these individuals and those who surrounded and supported their efforts, but ultimately this approach disunited the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, a majority of whom never supported such actions, and appears to have been the death throes of the radical movement that started on the factory floors. This attempt at building a revolutionary-electoralist strategy seems foolish today, but perhaps at that time, in the context of elected judges able to act antagonistically against the police and capital, it looked different. Nonetheless, while it was not without its faults, the League appears strongest and most successful in the place it began, the shop floor. Though in time the factories did run away (or more accurately were violently wrested from Detroit by their owners), the Revolutionary Union Movements were the roots of a stillborn revolutionary Detroit, one that grew many branches.

Today, in Salt Lake City, the city government has moved to tax residents to support local capitalist Ryan Smith’s vision of a downtown sports/entertainment district. Also, this year, the Larry H Miller Company broke ground on the Power District, its own several blocks-wide redevelopment project on the city’s west side, crowned by a new Major League Baseball stadium, and also supported financially and politically by state and local government. Where auto manufacturers drove New Detroit, the New Salt Lake City is the work of car dealers and tech billionaires.

It doesn’t seem like the League of Revolutionary Black Workers or any of its subsequent or allied organizations actively fought the New Detroit project, which was instead able to fail on its own terms. Instead, they worked to provide a positive alternative; a city which could boast a strong working class which had strong unions in the workplace, established media institutions that spoke to and for it, and a representative local government which was aligned with the interests of the people, not the police and bosses. In Salt Lake, however, we have none of those things, yet. Emergent workplace organizing, minimal tenant organizing, and countless lost fights against gentrification mark the halted, unrealized, potentials of a revolutionary urbanism in Salt Lake.

In an article from last year, From Anti-Gentrification to Revolutionary Urbanism, I spoke of the need to build out from the primarily negative position of anti-gentrification to a positive program of urban revolution. Building revolution out a multi-faceted front of mass, autonomous, working class organization based in everyday life and oriented towards urban reconstruction on its own terms is no simple task, but the work of the revolutionary black workers in Detroit during the 70s should be seen as part of the lineage of urban revolution which stretches back to the Paris Commune, and one we must take up in Salt Lake if we are to see the end of class, racial, and gendered oppression. To do so we must build working class organization rooted at home, work, school, and in the streets to actively combat the continued capture of our lives and our city by the capitalist class and the state. What structures (housing, work, educational) exist in working class life? What common issues or aspirations exist which could be addressed through radical organizing? What institutions should we strive to build presence in? How can we build a revolutionary vision of life in Salt Lake?

Addendum

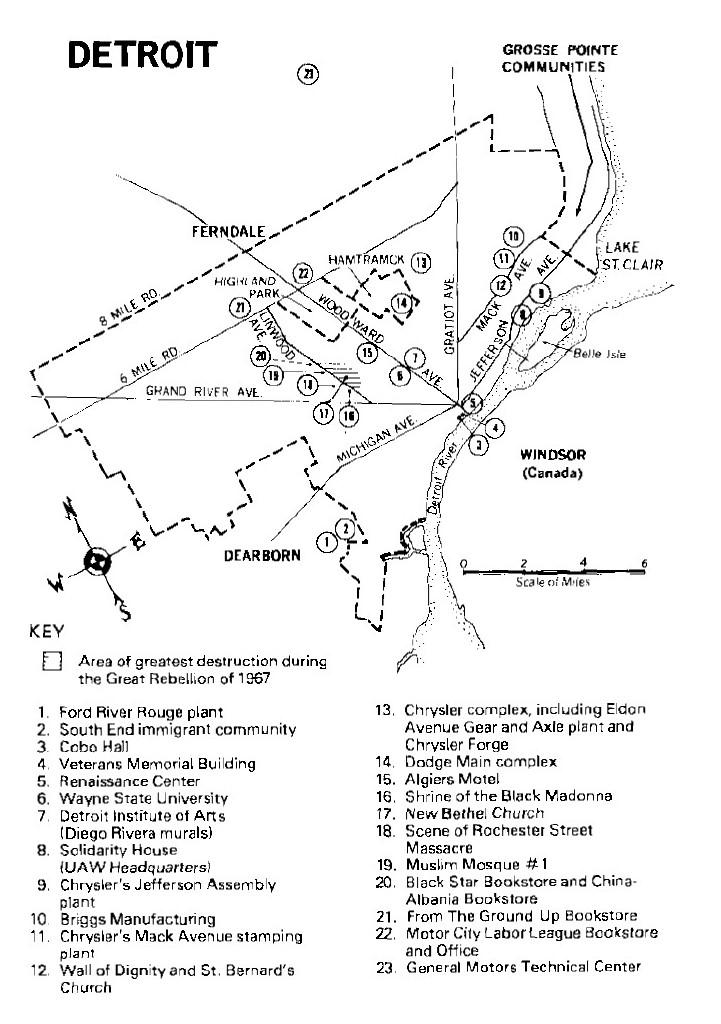

The above exploration focuses on organizing, institution building, and the project of building lasting power, but, as recent and historical examples reveal, urban revolution will also manifest in spontaneous uprising. Directly prior to the events explored in Detroit I Do Mind Dying, black proletarians fed up with years of racist discrimination and violence rose up in the Great Rebellion of 1967. Today, the ripples of the George Floyd Uprising continue to be felt and mark the continuing importance of riots and spontaneous uprising in the historical project of creating a free and equal society.

Please enjoy this map of the destruction during the Great Rebellion included in an edition of Detroit I Do Mind Dying, a true work of radical cartography:

All quotes are from Detroit I Do Mind Dying

Available here to buy and here to download