Reflections on Defying Displacement

Andrew Lee’s Defying Displacement is a wonderful exploration of contemporary struggles against gentrification. Placing gentrification in the context of the “Great Inversion” seen in many cities, where wealth has become reconcentrated in urban cores while the working class is pushed out into the suburbs, Lee’s book is far reaching and robust, covering many facets of gentrification as they’re experienced in cities across the world. What remains vague in his analysis, however, is a clear definition of who “gentrifiers” are. Lee’s most consistent use of the term refers to the new residents of gentrifying neighborhoods, those wealthier residents who can only move into an area once its original inhabitants have been pushed out. Based on this framing of gentrifiers-as-new-residents, Lee is quick to point to the rift within the working class between high- and low-waged workers, with the former being the gentrifier and the latter the gentrified. While this rift is very real, the influx of high-wage workers, though clearly caused by gentrification, cannot be said to cause gentrification. This article pulls together analysis of an actively gentrifying neighborhood and communist theory on the composition of the working class to tackle the question of identifying who can be called gentrifiers, and how understanding the composition of the working class can help us broaden the scope of our struggle without loosing sight of gentrification and its harms.

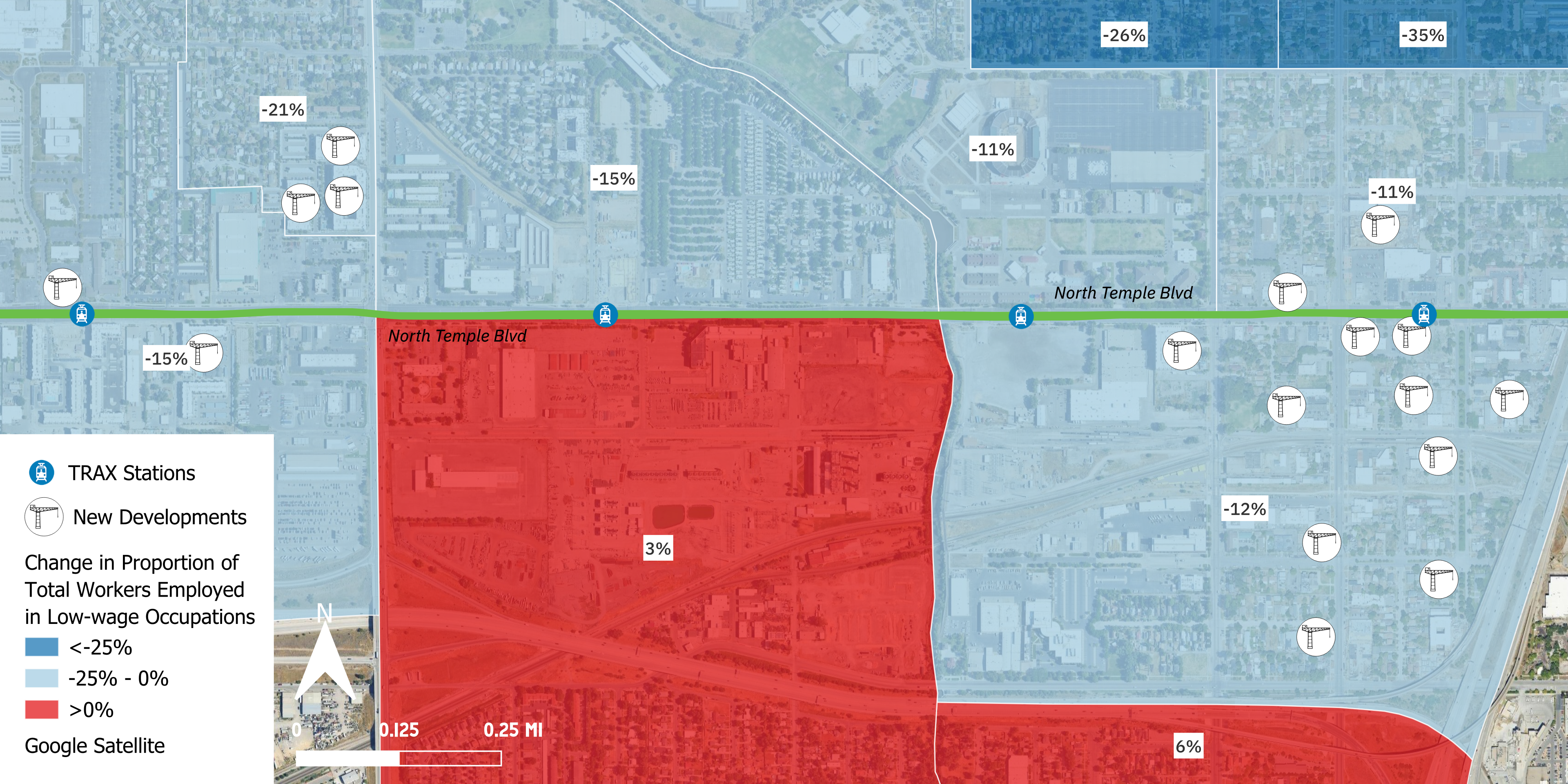

In the historically working class neighborhoods along North Temple in Salt Lake City, ongoing gentrification has seen the class composition of the surrounding area change drastically, with the proportion of workers employed in occupations with local median incomes of over $50k increasing from 11% in 2010 to 24% in 2020. This change is even more pronounced in census blocks that saw redevelopment projects over that time period, where the proportion of workers in high-waged occupations increased from 13% in 2010 to 28% in 2020 (US Census). As the neighborhood is redeveloped, the class composition of the neighborhood becomes increasingly skewed towards high-wage workers in occupations in management (4% of all workers in the area in 2020), finance (3%), tech (4%), and healthcare (7%). These trends are far more pronounced than the county average, which saw the proportion of low-wage workers in the workforce decrease from 70% in 2010 to 65% in 2020.

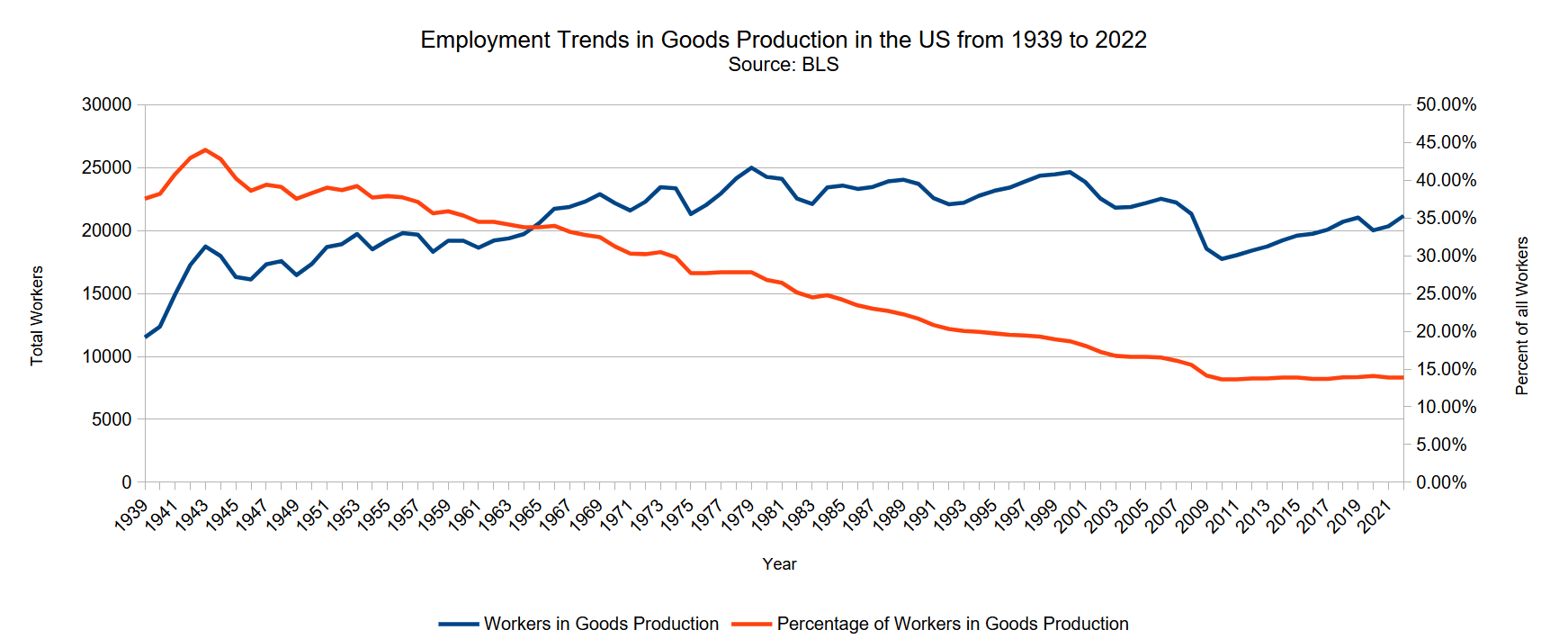

This observation is backed by the work of theorists Jasper Bernes and Phil Neel. Bernes’ essay Logistics, Counter-Logistics, and the Communist Prospect points to the growing irregularization and casualization of work which in turn makes proletarians increasingly antagonistic to the historic calls of the classical workers’ movement to seize their workplaces and run them for themselves. Instead, Bernes argues, today, the scale and content of the means of production has foreclosed such historical possibilities, replacing them with the riot, the blockade, and the occupation. For Bernes, this is ultimately a question of reconfiguration, how revolutionary proletarians might reconstruct, or reconfigure, society into a “free association of producers.” This question has just as much relevance in our discussions about gentrification, but for the moment let us return our focus to the immanent analysis of class composition. Bernes comes to the conclusion that capital has split “workers into a ‘core’ composed of permanent workers (often conservative and loyal) and a periphery of casualised, outsourced and fragmented workers, who may or may not work for the same firm.” This rift in the class is seized upon by Lee in his understanding of gentrification, which sees “privileged and expendable workers” set against one-another. Understanding this rift in the working class is further backed by the work of geographer Phil Neel, whose recent work on pre-mature de-industrialization has called attention to the higher-level trends which lead to such stunted growth in the creation of a stable proletariat, the sort which the workers’ movement of old thought would soon become the majority. Drawing adeptly from an analysis of the composition of productive capital and the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, Neel further builds out his urban critique to include macroeconomic shifts in industrialization, where increasing productive output no-longer sees a related increase in employment in that production. This too can be observed clearly in the US, where productive output has continued to rise even as employment in productive industry has stagnated, and ultimately decreased dramatically as a share of total employment (see below).

While Neel’s recent work has explored these trends as they manifest in Tanzania and China, this trend in the composition of the working class is clearly global. It is these higher-level trends in the capitalist economy that lay the groundwork for local gentrification, which then mirrors the broader class composition. In another recent interview, Neel, speaking again about these very trends in employment, and ultimately the working class, identifies that the economy is increasingly dependent on low-employment sectors for economic growth, leading to “a “dual labor market” dominated by service work, and in which these services are divided between a small minority of high wage jobs and a vast majority of low wage jobs, the latter often serving the former.” While the form that this economy takes may vary from place to place, gentrification certainly fits this type. The sort of economy gentrification produces is often reliant on tech, tourism, and the joint FIRE sector (Finance, Insurance, Real Estate), which all generate the dual character of low- and under-employment.

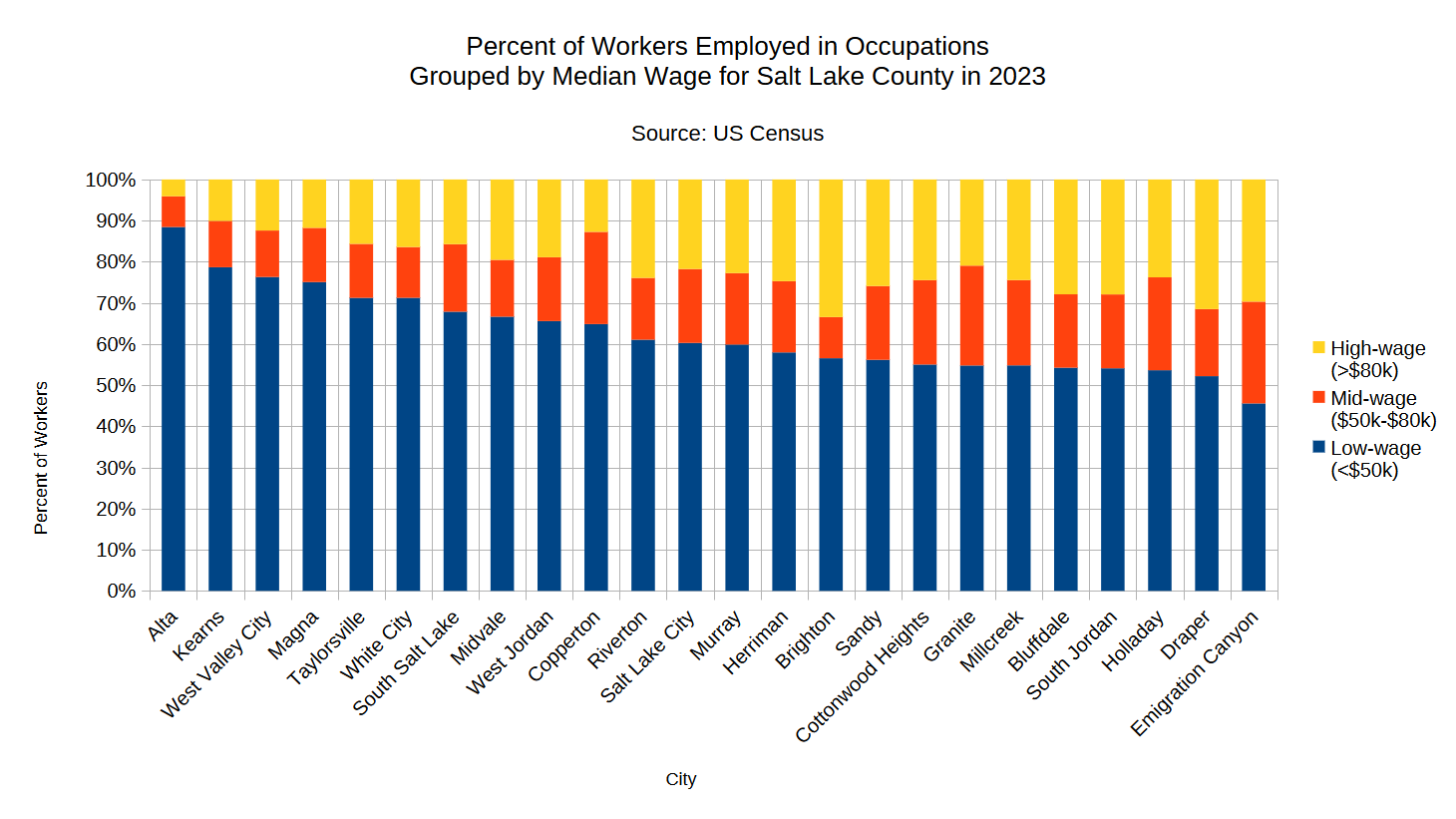

So how does this help us identify who the gentrifiers are? Throughout his book, Lee identifies tech workers, professional workers, high-paid workers, and the nebulously defined “privileged workers” as gentrifiers. These categories are often accompanied by a racial analysis, which identifies people-of-color with low-waged work and white people with high-waged work. As Bernes and Neel highlight, the broad strokes of these distinctions are well-founded, as the working class is increasingly split between a growing mass of casual/irregular workers and a narrowing concentration of increasingly technical workers, the result of high-level trends in capital accumulation. In Salt Lake, at least, insofar as this reality is represented by employment in low-/high-waged occupations, this split bears out along racial lines as well (the cities in Salt Lake County with the highest proportion of employment in low-waged occupations are also the cities with the highest proportion of people-of-color, namely West Valley City, Kearns, Magna, Taylorsville, and South Salt Lake).

So gentrifiers are white workers employed in high-waged occupations… this is a workable definition and in many ways validates the legacy-term YUPPIE (a young upwardly mobile urban professional), but there remain aspects here which are troubling.

Firstly, this definition cuts against gentrification as a process of class struggle, instead reframing it as intra-class conflict between estranged segments of the proletariat. Capitalists-vs-workers becomes workers-vs-workers, as the rift between low- and high-waged, casual and secure, and POC and white, become the new dividing lines. Throughout his book, Lee is critical of seeing tech workers as members of the working-class, going so far as to claim that identifying both tech workers and undocumented workers as workers “reduces working-class politics to a politics of identity in the crudest way” (pg 74). This claim is bolstered by the existence of employee stock-offerings at some tech firms which clearly muddles the waters of capital-ownership, though arguably only as far as homeownership also does (a housing relation which is commonly found among the North American working class, especially in Salt Lake). While the rift between workers remains large, class is ultimately defined by one’s relation to the means of production, not ethnicity nor income. As such, to reaffirm gentrification as a process of class struggle, we must tackle a second point, agency in production.

Insofar as a gentrifier would hold responsibility for the process of gentrification, we must ask who produces gentrification. Drawing from Salt Lake’s own history of gentrification, and this blog’s analysis of it, several actors come through clearly. The first and most important player are property owners; neither rent-increases, eviction, nor redevelopment occurs without the decision of the relevant property owner. Another key player is the finance industry; gentrification cannot occur without considerable new investment which requires major contributions from private finance; state-led efforts to create “opportunity zones” are an example of this reality, and also lead us to another major actor, the state. Whether in its local, regional, state, or federal forms, the state is an indispensable part of gentrification, crafting the laws and codes (including zoning, tax-structures, public investments, and plans) which either court, or otherwise support, capital’s growth in a given neighborhood. In Salt Lake, the redevelopment agencies, transit authority, and state and local governments have all played important roles in furthering gentrification. To summarize, gentrification is made by the owners of capital (land, finance, means of production, etc.) and the capitalist-aligned state. It may be the high-waged technical workers who are afforded the incomes necessary to live in the redeveloped neighborhoods, but to claim that they are the ones who cause gentrification would be erroneous. Conflating high-waged workers with capitalists appears to be a bigger sin than arguing that undocumented workers and technical workers are both workers.

Building from this position, anti-gentrification must then arise from the working-class fighting back against capital. We must understand the composition of the working class to better organize it, building it into a class that can fight for itself and ultimately reconstruct human society. Reframing gentrification from intra-class struggle to inter-class struggle clarifies the social relations we must tackle to move beyond localized fights defending shrinking ethnic enclaves and into generalized class struggle against capital. Better understanding class composition will allow urban revolutionaries to craft tactics and strategies that affirm class autonomy on the road to proletarian revolution, allowing anti-gentrification to become revolutionary urbanism. Models for such a class struggle include organizations of workers like the League of Revolutionary Black Workers of Detroit in the 70s and the growing tenants union movement today, which has already seen victories opposing gentrification in places like Kansas City. Class power emanates from the creation of autonomous, democratic, mass proletarian organizations rooted in working peoples’ every day lives. While most labor unions have become co-opted by capital, strategies to reintroduce militancy to the resurgent labor movement exist, and must be taken seriously if the working class is ever going to become strong enough to overthrow capital. Similarly, territory-based organizing promises untapped opportunities to organize workers in economies marred by precarity and irregular employment, allowing working-class power to be built even in places where organizing at the point of production proves difficult.

The tenant and neighborhood organizing strategy, especially combined with workplace campaigns, might have more long-term potential in some of these suburbs, especially since it will provide more useful infrastructure if firms were to close down or engage in mass layoffs or if there is some new climate catastrophe. – New Battlefields, Phil Neel

To break out of cyclical struggles to defend the crumbs left for workers by previous processes of capitalist accumulation, the balance of power between the proletariat and the capitalists must be altered, only then can we defeat gentrification and take back the city.