Years after Washington Square was occupied by activists in protest of plans to shutter the downtown Road Home shelter, the land the shelter once sat upon has a new name, the Luma. The reclamation of this land by capital was long in the making, tracing several decades of struggle over the future of downtown. But this fight has not been confined to this one parcel; the one-sided class war which culminated in the Luma, the Rio Grande Plan, an “Innovation District”, and more, oversaw the violent expulsion of the unhoused from this downtown adjacent district.

As far back as 1998, Salt Lake City began to plan the redevelopment of the historically industrial, commercial, and working class neighborhood surrounding the Rio Grande train depot. In the period following the depot’s abandonment, the construction of the I-80 through the working class neighborhoods directly west of the area, alongside generalized disinvestment, created the conditions for the neighborhoods’ abandonment to those capital saw as unfit to exploit through employment or care for through social programs. As the unhoused population in Salt Lake grew, following prolonged economic decline and rising housing costs, the neighborhood surrounding the Rio Grande depot increasingly became a central location for unhoused individuals to find resources, shelter, easy access to transit, and all the amenities of downtown. But as this concentration grew, accompanied by petty crime and drug use, the city decided it could no longer tolerate the consequences of its ongoing presence dissuading gentrification. Launching Operation Rio Grande (ORG) in 2017, Salt Lake City called on police agencies across the Wasatch Front to open a new front in the war on drugs in downtown Salt Lake. Overwhelmingly targeting individuals for low-level misdemeanors and infractions (think jaywalking, public camping, public urination, etc.), ORG served only to overcrowd the valley’s carceral facilities and ultimately lead to ~80% of the funding allocated to ORG being used for policing, jail beds, and court costs. Out of the three phases pursued in the ORG, moving from enforcement to treatment to employment, only the first, most violent, of the phases could ever claim success on their terms, assuming one counts the over 5,000 ORG-related arrests as a success (many of which were then immediately released upon booking due to crowding at the jails). Even the ACLU Utah criticized the “law-enforcement dominance of ORG”, citing this approach as the reason for its inability to address any of the real social issues at work here, instead opting to simply “criminalize homelessness.”

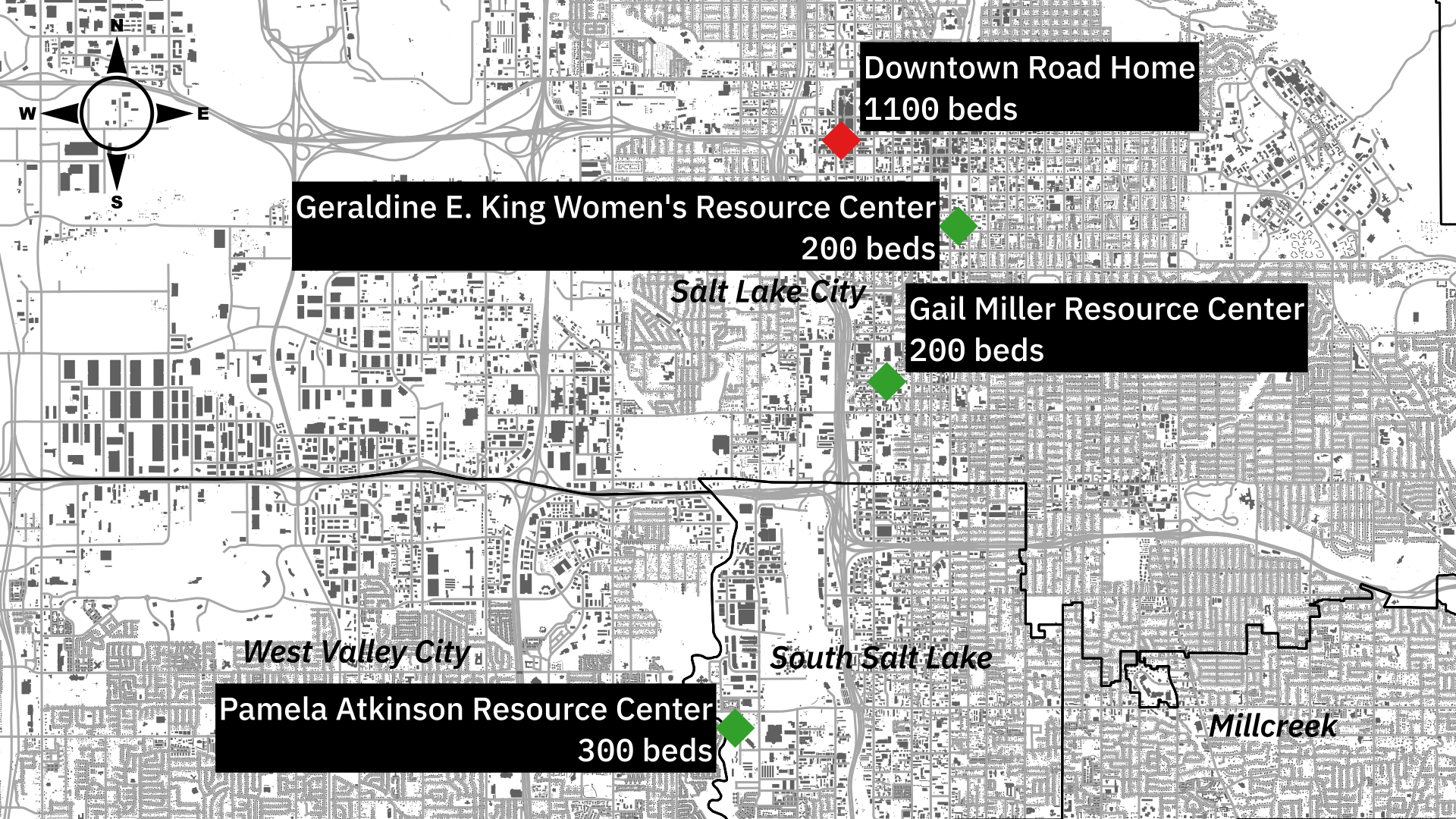

In the context of this failure, the two-year Operation ended with the closing down of the downtown Road Home shelter and the opening of three new, “dispersed”, shelters (referred to as a “scattered-site model”). Shown in the map below, this is where the project of urban reclamation truly came to the fore:

Alongside a 36% reduction of total beds, from 1,100 down to only 700 (and this in the context of ever-rising numbers of unhoused people), this new model pushed available shelter out of downtown Salt Lake City and south along State Street, with the largest of the new shelters built four and half miles away from the downtown site, deep in the working class city of South Salt Lake. This displacement or resources and people, following their abject criminalization for the simple fact of not being able to afford a rent in a city which every year becomes more and more unaffordable, is nothing short of class war waged on the property-less class, that class of capitalist society that has only its labor to sell for a wage, and short of that, has nothing.

But the failures of Operation Rio Grande were only a concern to activists and the bleeding-heart liberals at the ACLU. The city was quick to court capital to step into the vacuum it has created through police violence. While the groundwork had already been laid with the creation of a SLCRDA Redevelopment District in 1998 (the Depot District) and the establishment of counter-cultural type spaces like the two Artspace buildings located across from the Rio Grande depot, it would take several years, numerous state incentives, and a (now-slowing) rise in new development for capital to really begin flowing back into the neighborhood. Working to bridge the ongoing rampant and fast-moving gentrification of North Temple Boulevard with the post-industrial redevelopment of the Granary District, the reclamation of the Rio Grande would soon find new friends in the growing YIMBY movement. Rising out the demographic inversion of the North American metropolis which is overseeing the reintroduction of YUPPIES into the city centers their parents fled from during white flight, the YIMBY movement has astroturfed support for developer capitalists and corporate landowners by espousing faux-progressive rhetoric full of shallow claims of environmentalism and anti-racism.

Apparently unimpressed by the pace that the local ruling class was gentrifying the neighborhood, a team of YUPPIES came together to create the Rio Grande Plan. While the plan touts itself as a solution to the cities very real east-west divide (the result of redlining and racist urban development), it’s more akin to a real estate scheme dressed up as a big idea. The main concept is to bury the freight and commuter rail tracks which run a block west of the abandoned depot, placing them in a “train box.” Citing similar projects in Denver, Reno, and Los Angeles, the plan claims such a move would reconnect and revitalize the area. Reading through the plan, however, most of the benefit would come from the 75 acres that would be “opened for redevelopment” by removing the Union Pacific rail yard and adjoining industrial facilities. Even the Utah Transit Authority’s new bus garage is said to be a “potential future development.” Imagining the total expulsion of industrial land uses from the area, the plan visions an “entire new city district… [with] new green spaces, offices, hotels, entertainment venues, university facilities, a permanent public market, churches, and more.” In a map included in the plan, the authors label four nearby blocks as being “private redevelopment opportunit[ies]” a clear sign of whom they’re working for. All of this, they say, would inflate the value of the affected parcels from $17 million to $2 billion. With zero mention of housing affordability, the racial discrimination that the east-west divides in this city cannot be understood without, or the brutal acts of police violence which cleared the neighborhood for their pleasure, and placing the plan as a necessary component in realizing the recent billionaire-led sports stadium proposals, this effort is an encapsulation of the YIMBY position. Ignorant (perhaps willfully so) of the history of the site, the Rio Grande Plan seeks to finalize the reclamation of the Rio Grande neighborhood for capital. Justifying itself in the language of real estate capital (over 100% increase in land value and massive redevelopment) and the projects real estate envisions for the city’s near future, the plan cloaks itself in the real issue of spatial segregation to push for the further entrenchment of gentrification in Salt Lake City. The barriers to east-west connection must be addressed, but not through continuing this legacy of violence and displacement. Years after Operation Rio Grande, its dream of a city rebuilt for the upper classes lives on in the Rio Grande Plan.

From heavy industry to mixed-use redevelopment, the Rio Grande neighborhood has seen the dual ends of capitalist urban policy; industrialization giving way to disinvestment leading to poverty resulting in violence reopening it up to investment. Neither the Road Home nor the train box are what the working classes of Salt Lake need. Shelter and transportation must be built to meet the needs of the residents of this city, who today struggle with rising rents and cost-of-living, both of which are sure to rise further with the creation of new elite sports facilities and the looming Olympics. At the time of writing this there is no burgeoning movement to claim the working classes right to the city and fight for a reordering of urban space, the author supposes that critique of the unfolding capitalist city will have to suffice.